Tomorrow’s Marketing Must be Smart—and Romantic

When you ask a marketer about the future of the business these days, you get very different answers. One person will tell you that marketing is a precise science that defies the idea of the “big idea” and relies on big data, while another will insist that marketing is defined by the quality of listening and storytelling, a creative discipline that must dream big to project and generate future value for its stakeholders.

On the one hand, marketers are forecast to spend more money on technology in 2015 than IT departments. They have amassed a vast amount of data and have more tools to aggregate, analyze, and act on them as ever before. They are privy to customer conversations and have access to new ideas at unprecedented scale. On the other hand, privacy issues have made us as consumers and citizens acutely aware of the fragility of our identities. Some of us have begun to alter our online behaviors, up to the point where we prefer silence over expression, as our freedom of speech is suddenly threatened by unlikely foes: digital (self-)surveillance and an often vicious online mob that is quick to jump on the latest “shit storm.”

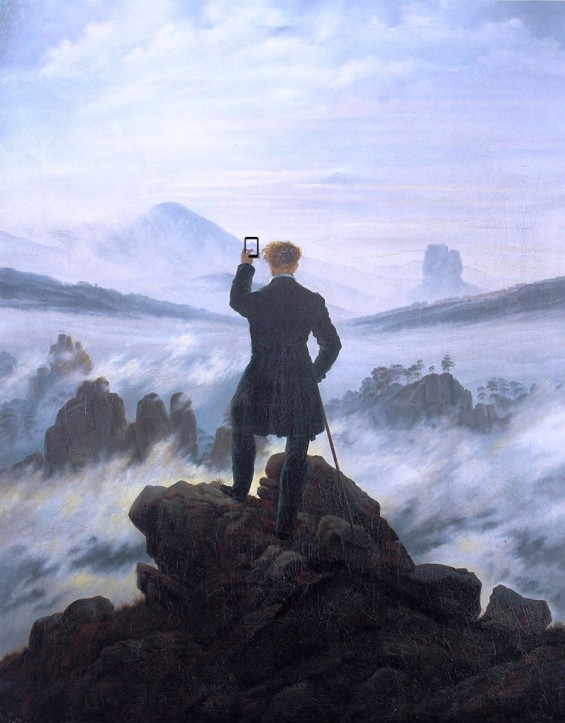

In light of “tech-lash” and digital overwhelm, we are reminded of our thirst for meaning and are craving a sense of transcendence that points to something greater than the next click. Increasingly, we are longing for longing, for a communion beyond community, for catharsis not consumption, for authenticity instead of some data-based objective truth.

From constant connectivity to feelings that don’t last

Indeed, I believe we are moving from the smart age to a new romantic age. The smart age has been one of instant gratification, real-time feedback, and adaptation. The goal was to accumulate maximum knowledge about customers and their preferences and behaviors, to quantify all touchpoints, in fact, to quantify everything, in order to then target and deliver with the utmost precision.

Succeeding the broadcast era, the smart age bore a social model of marketing that catered to newly empowered consumers and capitalized on user-generated content, making sure that customers, too, were provided with maximum knowledge. Fluid and super-flexible in its approach, smart marketing quickly adapted to ever-changing market circumstances. Everybody strove to be the Google of their category. Think of Zara, the fashion retailer, and how it created entire clothing lines on demand. Or the rapid-response Old Spice video ads that perhaps marked the pinnacle of the “your brand is a conversation” paradigm that the Cluetrain Manifesto had so clairvoyantly predicted in 2000.

The marketing mix ideally had to change every day, every hour. From the reassuring consistency of their messages marketers moved to the vibrancy of conversations, from differentiation to ubiquity, from big moments to an array of small hyper-targeted, results-driven interactions. Smart marketing crowdsourced and democratized; it was inclusive, open, agile, and conversational. It became “newsroom marketing,” with community managers replacing campaign managers, and a growing cadre of journalists joining marketing teams as “content strategists” to drive and join social media-amplified stories.

Now, a few years into this brave new smart world, we’re slowly beginning to realize what we are losing in all that incessant chatter, with corporate conversationalists on either end. When everything that’s said is recorded and exploited, when everything’s explicit, rehashed, and hash-tagged, we lose a sense of aura, exclusivity, and elation. When everything is predictable and automated, we abandon the thrill of strangeness outside of our “filter bubbles,” of unfamiliar experiences that have the potential to disrupt our daily lives and grant them an awesome shock of meaning.

This new demand for meaning has dramatic effects on the economy of attention that constitutes the marketing arena. We like convenience and comfort, but we love brands that offer us unexpected beauty and friction. We look for rebels who punctuate our routines and offer us not just purpose and personalization, but a heavy dose of punch-drunk love. We want experiences that are unique and precious; experiences that can’t be scaled and must not be optimized either. In other words, we want romance, the ultimate insurgent in a regime of maximizers and optimizers.

The power of the unknown

Brand consultancy Landor proclaims the new branding paradigm of “TMI” (too-much-information), but I think the opposite is true: we secretly appreciate the allure of not-enough-information. For the very moment we know too much is the end of romance.

New Yorkers recently were all buzz about a secret club dubbed “Spring Street Social Society” whose mission it is to bring strangers together in “unexpected spaces” around a cabaret-style artistic program.

UK-based Secret Cinema operates in similar territory, showing interactive, participatory “mystery screenings” of seminal movies, from Casablanca to Blade Runner to the Grand Budapest Hotel. Movie and locations are disclosed to viewers only on short notice. Fabien Riggall, Secret Cinema’s founder and CEO, says he wants to bring the romance back to the movie going experience and provoke strong emotional reactions. He is driven by the desire “to create a spectacle, a dream, another world we can play with, how the world might be.”

Both companies have taken the practice of “unboxing,” known from tech products and fast becoming a critical ingredient for online retailers, and have made it the product. The unwrapping of gifts is more valuable than the gift itself. In a time when transparency is the norm, mystery attracts the utmost attention. Transparency dwindles against the thrill of the curtain-raiser—and the even greater thrill of the curtain staying closed. In the end, it doesn’t really matter which movie Secret Cinema is showing. In the smart age, the algorithm was a secret. In the romantic age, the secret is the value proposition.

Intimate and beautiful

We’re witnessing the return to intimate experiences at human scale, to unique, singular moments that don’t (need to) scale. “Take, for example, dinner series such as Death over Dinner series (no one dies, but all guests converse about the dignity of a good death), or Kitchensurfing, an online platform that connects chefs and diners for private dinner gatherings. Or take the recent buzz about Ello, which positions itself as the anti-Facebook, as its pure, more intimate, and denser alternative that goes deep before it goes wide. Ello’s manifesto—with its warm, human tone—was a big part of its appeal and initial explosive growth. And Somewhere, a new professional online network, offers a romantic alternative to LinkedIn: instead of linear resumes and an accumulation of credentials, it treats our work identities as stories, allowing users to present about their unique talent and personality rather than proving that they fit (in).

Romantic brands serve as idiosyncratic curators of the strange, eccentric, and whimsical. Other examples include “concept shops” such as Broken Arm that are becoming popular in Paris, with cafes, curious items, clothing and a desire to make the shopper think.” Or Maria Popova’s Brainpickings blog, a “human-driven machine for interestingness,” as she calls it, which serves as a tastemaker recommending select books and articles to her loyal readers. Both services resemble the good old hotel concierge and are, in essence, the anti-algorithm: collected by humans for humans. Accessible, personal, and highly subjective.

Our un-quantified selves

All these brands are wrapped in an air of nostalgia, a strong desire to connect back to a true sentiment, a profound truth that we may have lost in the busy comings and goings of our hyper-connected work lives: a yearning for something greater than our quantified selves.

However, romantic marketing doesn’t mean a backward model of marketing that is purely based on sentiments and intuition. It’s not an amour fou, as the French call it, the pipe dream of an unreasonable mind, devoid of strategy and calculus. It doesn’t want to simply return to archaic pre-data truisms. Rather, it will remain bipolar, yet more accentuated than before. The challenge and the opportunity ahead will be to create “smart romanticism”: using the data and intelligence at the marketer’s disposal to create romantic experiences rich with emotion and meaning that honor our un-quantified selves.

The sweet spot for both consumer and enterprise brands will be to reconcile smart technology with the imagination of a romantic. Why not combine Big Data and big ideas, big science and big dreams? Why not usher in what William Gibson’s cyperpunk 1984 novel Neuromancer projected as the marriage of cyberspace and romance, as, according to one reviewer, “a fusion of the romantic impulse with science and technology”?

Innovative marketers have always used both science and art, but the smart-romantic ones now do so not to demystify but to mystify, not to make everything explicit, but to create mystery and moments of inexplicable magic. They leave room for serendipity because they know that if it can be engineered, it’s not a brand. They don’t market just to move products; they do it to make meaning; not simply to generate impressions, but to impress themselves on the world.

The ultimate hack

We are indeed experiencing another “great disenchantment,” a term coined by the economist and sociologist Max Weber in 1919. Datafication seems to be pushing us to another trigger point for a new romantic counter-movement, this time heralded by the new poets, the new meaning-makers, of our time: marketers.

Like no other discipline in business, marketing has the power and responsibility to be the great enchanter, a modern medicine man, a magician rather than a data scientist or spreadsheet bureaucrat. Marketing can again provide us with the hope (or the beautiful illusion) that another life is possible. But this time the beautiful illusion is even more important because data and transparency are designed to constantly disillusion us: when maximum clarity and objective truth narrow our options, creating alternate realities is a truly humanizing act.

In the data-driven world of big, the time is ripe for the grand, albeit at intimate scale: heavy sentiments in small moments, niches that offer the great escape. As a powerful escape artist, marketing can lead the way. It can be the haven for misfits, pirates, renegades, rebels, poets, or mash-up artists, and cultivate mysterious sub-plots to the streamlined, algorithmic meaning-making machines. In this new digital-romantic age, it is—to borrow a term from William Gibson—the “ultimate hack.”

Published with permission.

This article was first published in Paul Writer’s magazine- Marketing Booster (Issue: Jan-Feb 2015).