Leadership as the Possibility of Another World

A conversation with Tim Leberecht

A conversation with Tim Leberecht, author of the book “The Business Romantic: Give Everything, Quantify Nothing, and Create Something Greater Than Yourself”

Isn’t the modern style of management more comparable with the Enlightenment: rational, objective, measurable?

Following the axioms of the age of reason and enlightenment, modern management is bent on constantly reducing the space for the unknown, on the basis of an objective, empirically proven truth. “We can only manage what we measure”— for many managers this formula has become the last safe harbor in an increasingly complex world.

In contrast, romantics want to make the space for ambiguity, the space for the immeasurable, non-comprehensible as large as possible. For them, doubt and opacity are more important than total knowledge and radical transparency. “I will not reason and compare: My business is to create,” as the 18th century poet William Blake once wrote. Romantics want to feel more, and business is their ultimate adventure.

They celebrate ambivalence, contradiction, the principle of hope. Many managers scoff: “Hope is not a strategy.” Wrong! Hope is the best possible strategy for it is the greatest intrinsic motivator and a powerful tool for getting others onboard. In fact, hope is an economic necessity, and so are aura, mystique and emotion. Without them, a company and its brand will become soulless automatisms—and rather easy for competitors to copy. As I write in my book: if you can engineer it, it’s not a brand.

Why is it so important to bring beauty to our work?

Romanticism strives for beauty, which is the epitome of the inexplicable. Beauty can’t be objectified. It solves no problem, and is therefore in direct opposition to the utilitarianism of traditional economic activity. It has both an aesthetic and experiential quality: as a sign of the metaphysical and as a critical moment of insight. It serves as a hint that there is always more that we can see, that tangibles aren’t enough for happiness.

Beauty is the difference between a productive and a fulfilled life: a life full of emotion and intimacy, adventures, and unexpected surprises. A romantic life. But there are also more pragmatic arguments for more beauty in business, such as results from brain research that correlate the subjective perception of beauty with positive creativity and productivity.

Why do you think that feelings are so important in business?

We have divorced business from many of our emotional, intellectual, and spiritual needs. With The Business Romantic, I propose that we broaden our perspective and bring our full selves to work—not just as hyper-efficient productivity machines, but as the enigmatic and struggling individuals that we are.

We must reclaim the language of business—which has infiltrated so many, if not all, aspects of our lives—and expand the common vocabulary of efficiency and productivity with new definitions of what it means to do business together, to be in a good company. Emotional intelligence, a happy workforce, and meaning should be the end, not the means.

Every company faces the same two challenges: how to attract and retain top talent; and how to create products, brands, and experiences that people truly love. I believe that romance is a powerful way to address both.

In fact, I would argue that romance is the ultimate differentiator in a world of optimizers and maximizers. When every company is doubling down on perks and purpose, romance is “the third place” and can make the difference. I’m talking about the adrenalin rush we experience in moments of unexpected challenges that remind us of our full potential and make us feel fully alive, and the fascination of cultivating our professional alter egos or meeting strangers. It’s these hints at the possibility of another life that create romance.

Unlocking the potential of Business Romantics at work is hugely valuable: Romantics usually dream big dreams AND get things done. They form strong bonds and show real commitment; not just passion that might flame out after a series of passion projects. They build a more collaborative, humane culture that will ultimately be attractive to customers. By humane I don’t mean nice or friendly, I mean intense and all-in, a culture where everyone is vulnerable and has skin in the game. A culture where everyone is constantly striving for significance, permanently unfulfilled but motivated by the possibility of greater meaning.

Romance gives employees and customers a reason to commit and re-commit every day, but it also provides something that is perhaps even more important: a sense of meaning and delight that goes beyond the usual market mechanics. It will not only make companies more successful but also our lives as employees and consumers more fulfilling.

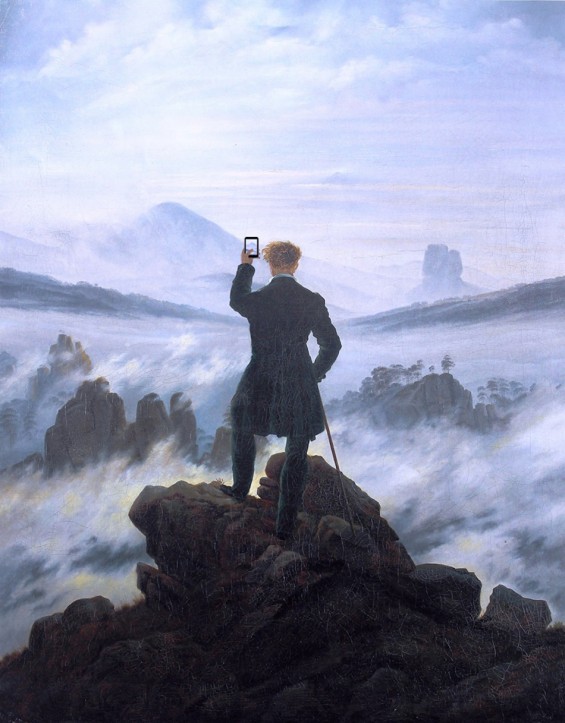

Image: Kim Dong-Kyu, based on “The Wanderer in the Fog” by Caspar David Friedrich, beautifuldecay.com

Romanticism was a counter movement to the Enlightenment, the age of reason. Do you recognize parallels in a world of new information tools that analyze and quantify?

Our networked era inevitably leads to quantification and automation. In the not too distant future, our very identities will be little more than data profiles that are always one step ahead of our sensibilities and intentions. Others will know us better than we know ourselves. And then there are of course virtual and augmented reality technologies going mainstream, as well as the rise of robotics and artificial intelligence, with all the possible consequences.

Intelligent machines will be able to think clearly—but will humans still be able to feel when our lives are governed by algorithms? We must defend the freedom that allows us to be imperfect beings. We aren’t just machines that provide accurate results. We are social beings and feel attracted to companies because they are messy, vital forums for social exchange and open-ended experiments.

A fully automated, process-driven, predictable economy will quickly become inhumane. We must once again learn to appreciate what we can’t measure. Therefore, we need a new romantic movement—rich with mystery, ambiguity and emotion—to protect the obscure and unpredictable against the regime of radical transparency, frictionless performance, and total knowledge. How can we use new digital technologies for enchantment? Is the second machine age the last one or the first one to actually give us a “third place”?

Why do we need surprises in business?

At the workplace, surprises revitalize and strengthen the existing business culture by reminding us of what’s possible and that we’re not really in control. They nudge us, awaken us, and create moments of authenticity because what we feel, in that very moment, is truly genuine and unfiltered.

Surprises play an increasingly important role in the customer experience, too. Most customer experiences are designed for convenience and comfort; but unexpected disruptions that challenge our cognitive models and preconceived notions give us the greatest joy and meaning. In a New York night club called “The Box,” for example, customers who have bought the most expensive tickets find themselves in the kitchen doing dishes.

You claim that Virgin founder Sir Richard Branson or the late Steve Jobs from Apple are romantic heroes, characterized by an aura of mystery and emotion.

First of all, we must not renounce the concept of heroes. We need them to embody our desire for an ideal state, constantly reminding ourselves of the impossibilities of human life. Heroes are the messengers from another, better world.

But we are no longer looking for heroes just at the leadership level, and they also don’t have to be lasting and flawless figures. In an economy that is increasingly based on collaboration and cooperation, individualistic, lone warriors are becoming obsolete. Instead we need leaders who can inspire others and create space for their dreams and passions. We need heroes who enable others to be heroes, as the management thinker John Hagel put it.

“The main task of managers is to achieve results, and to realize the purpose of their business.” Do you agree with this?

This is too narrow for me. Results are, like everything else in business, floating moments that dissolve quickly. And what really is the purpose of the enterprise? Shareholder value? This concept appears more and more limited, especially since introduction of the “Triple Bottom Line” (profit, environment, social responsibility).

Companies are the most important social institutions of our time. They shape our identities, in no small measure, and they are sense-makers. Knowledge workers spend up to 70 percent of their waking hours with work. “Work is where we make or break ourselves,” the American poet David Whyte observed. Business leaders and managers have a unique opportunity to act as makers and arbiters of meaning, maybe even as “healers.”

Leaders don’t need to know more than their employees. But they must know what they don’t know and hire people who know more than they do. The best leaders are brave (and smart) enough to admit their own vulnerabilities.

So, what distinguishes a good manager from a good leader?

A good manager defines, specifies, and sets an example. He or she listens, motivates, and manages to unleash the potential of their employees and grow it. A leader, on the other hand, opens eyes and hearts to new experiences. A good manager gets the best version of its employees. A good leader transforms his or her employees into entirely new people.

It seems that the principles of business romanticism may be easier for someone who enjoys a great deal of autonomy in their job to realize. Is that a fair assessment?

Without a doubt, autonomy is crucial for applying the principles of Business Romanticism. But the notion of autonomy can take various shapes. While most of the protagonists in my book are knowledge workers, one doesn’t have to be a start-up entrepreneur, senior executive, or a freelancer to instill one’s work with moments of romance. And what does autonomy mean anyway? The self-employed freelancer might enjoy a considerable amount of flexibility in terms of his or her daily schedule but is also expected to respond to clients at any time, which is actually infringing on the level of autonomy in his or her personal life. A CEO might have the power to determine how he or she spends his or her time and make decisions but is also constrained by his or her stakeholders’ often conflicting agendas.

You quickly realize that autonomy is relative, and in the context of Business Romanticism it is perhaps more helpful to think of it as the feeling of autonomy. Just as constraints are critical for spurring creativity and innovation, they are also the romantic’s secret weapon. Recurring, seemingly mindless tasks might represent the “little bit of suffering” that the romantic welcomes in order to find the sacred in the profane, to transcend the here and now with a belief in a greater truth that might reveal itself through the very commitment to one monotonous task.

This is the kind of ethos that craftspeople exhibit in their work, from the chef to the cobbler. There is a beautiful scene in the movie Locke where a construction manager—while his whole life is unraveling, including being fired—passionately insists on his moral obligation to get the job right: because the ‘small cracks’ in the ‘pure’ concrete can bring the whole world down, as he assures himself. I actually Googled ‘C6 Concrete’ after watching the movie! There is beauty in everything, we just need to find it. It doesn’t so much require autonomy over the task but autonomy over the way we view our work and frame our own narrative about it. Now, you might consider this a naïve thought and accuse me of “romanticizing.” Right on. That’s precisely my mission.

###

This interview is based on a translation of the author’s being interviewed by Alexandra Hildebrandt for the German Huffington Post (“Fels sein und Wasser”), augmented with additional original content. The English version appeared first in Revue Magazine for Next Society in August 2015 (part one, part two).