Cognitive Collapse Is Good For You

AI will make thinking easier and harder—and may prompt us to become more human.

by Tim Leberecht

On June 26 this year, I was sitting on a veranda in Atlanta, Georgia, when I heard a loud blast. It sounded like a bomb, or like thunder of a rare, seismic kind—but sharper, more metallic, more alien. It turned out to be a meteor crashing to Earth. Experts later determined it was 4.5 billion years old—older than our planet.

It was a close, visceral encounter with an object that had crossed into my time and space from another epoch entirely. The temporal equivalent of the “Overview Effect” astronauts describe when looking down at Earth, the meteor constituted a moment of awe that put my own perspective into perspective. Four thousand weeks—the average human lifespan—set against 4.5 billion years. Paradoxically, the comparison made my tiny life feel more significant.

I wondered if, one day, someone will look back at the early 21st century—the political turmoil, the depression, the viciousness, the pettiness—and see it all as trivial in the context of the larger story: the collapse of our humanity itself.

This is the End

Collapse is inevitable—or at least, so is hearing about it. Images of extreme heat, wildfires, and other climate emergencies are striking, accompanied by breakdowns across political, economic, and social systems.

Luke Kemp, a researcher at Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk and author of Goliath’s Curse: The History and Future of Societal Collapse, argues that “by looking at the 5,000 years of civilization, we can understand the trajectories we face today—and self-termination is most likely.” Joseph Tainter, in The Collapse of Complex Societies, traces collapse to the point when maintaining a civilization’s complexity costs more than it’s worth—when the returns on complexity turn negative. On a more uplifting note, Kemp points out that the downfall of empires looms large in history and popular culture, but for the majority of humanity, their collapse often had its upsides.

Defense and security expert Elisabeth Braw, in Goodbye, Globalization, bids farewell to the “flat world” and sees us sliding back into conflict between self-interested nation-states. And Clara E. Mattei, an economist examining the correlation between fascism and austerity—a mischievous invention of economists to accrue power, she claims—wants us to escape from late capitalism and in particular the widely accepted idea that there’s no alternative to it.

Even business and tech gatherings are flirting with fatalism: Hamburg’s Next Conference this September has chosen “This is the End” as its theme, perhaps poignantly, perhaps because it’s rumored to be the last edition.

Meanwhile, Western liberal democracy is under siege—not only from external threats such as “land-swapping” strongmen in Russia or the U.S., but from within. It has grown lazy, complacent, and self-righteous, forfeiting much of its moral legitimacy.

Cognitive integrity and “hypnocracy”

Yet the most insidious collapse is internal: the disintegration of our human faculties. AI is, depending on your view, either the cause (if you are a humanist) or the catalyst (if you are a nihilist). The problem isn’t merely that the world is collapsing around us—it’s that we are collapsing within ourselves.

In The Cognitive Threat—a podcast written and narrated in French by HoBB member Bruno Giussani—he and his expert guests examine the integrity of the human mind in an age of overwhelming information, AI, and neurotechnology. While they address disinformation and deepfakes, their main concern is cognitive sovereignty: our ability to attend, perceive, think freely, and decide autonomously.

“The new landscape will gradually be populated by things that look like humans, but are not,” Bruno told me. “A world where humans and artificial entities will coexist, interact, and co-evolve. AI will know each of us better and better. A chatbot that knows your priorities, your weaknesses, your secrets, your desires, even your bank account, will be almost irresistible. It will have the power to control what we think, what we do—in a way, who we are.”

Control. Manipulation. And ultimately, the erosion of what makes us human.

We’ve already seen the viral spread of fabrications—most recently, a faked orca attack on an instructor, or the AI-generated avatar of a Parkland school shooting victim interviewed by former CNN reporter Jim Acosta. Deepfakes compound into an alternate reality, meticulously curated for us by algorithms.

In his podcast, Bruno cites a very meta case in point: Hypnocracy, a 2025 book by the Hong Kong philosopher Jianwei Xun, introduced the eponymous concept as “a system that no longer operates through force or rational persuasion, but through the manipulation of collective states of consciousness.” In a hypnocratic state, Xun writes, “every event, every image, every word is part of a mechanism that does not merely represent reality: it replaces it. Simulation no longer imitates the real. It precedes it. It shapes it […].” Essentially, hypnocracy is “the regime to numb critical thinking,” as El Pais put it.

After Hypnocracy gained traction in certain intellectual circles, a journalist found out that Jianwei Xun was, in fact, a fictional persona. The book’s true co-author was essayist and editor Andrea Colamedici—listed only as a translator—who had written it in close collaboration with two AI systems.

The demise of critical thinking and conscientiousness

More troubling still are the long-term effects of digital technology—and especially AI—on cognition.

Critical thinking, a distinctly human capacity, is under siege. A recent MIT study on generative AI, alongside research on AI’s impact on essay writing, warns of “cognitive debt”: the notion that short-term productivity gains come at the cost of diminished reasoning, imagination, and memory. In classrooms, AI use is said to fuel a “poverty of imagination,” with unknown long-term effects on children’s cognitive and emotional development.

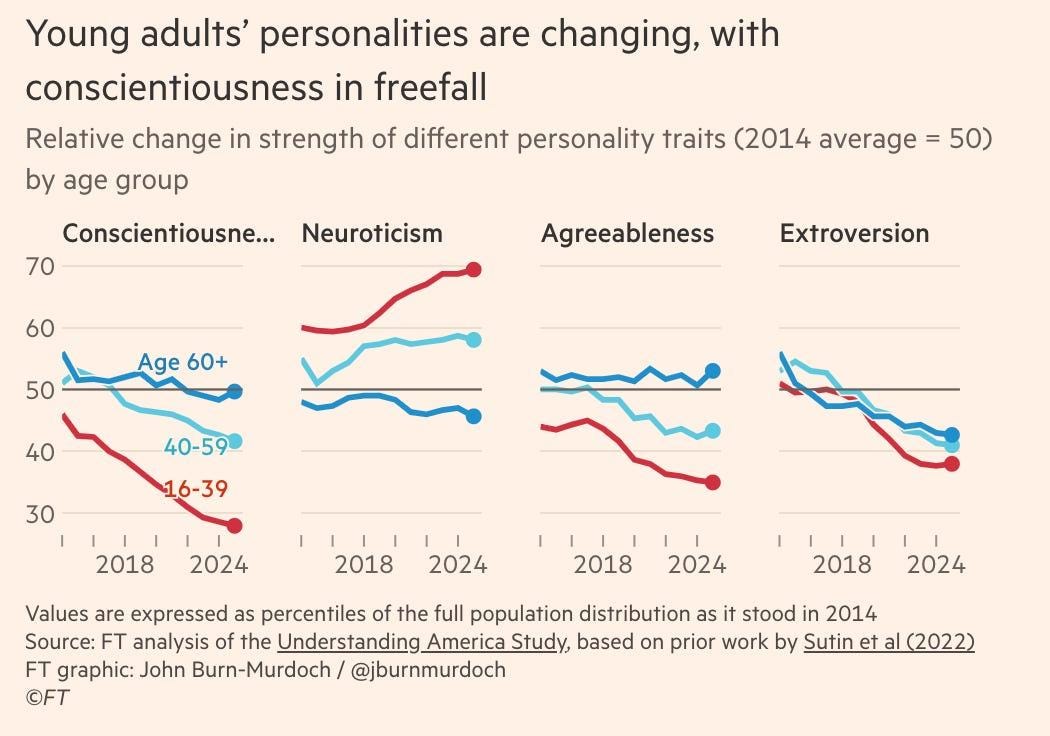

The 2025 Understanding America Study finds that Americans in their twenties and thirties report feeling more distracted, less tenacious, and less likely to follow through on commitments. In the Financial Times, John Burn-Murdoch bemoans this decline of “conscientiousness,” which he defines as “the quality of being dependable and disciplined, emotional stability or agreeableness.” He points out that conscientiousness is more critical for professional success, the health and duration of relationships, and longevity than someone’s intelligence or socio-economic background. The study also reports that neuroticism, as a function of increased anxiety, is on the rise among young adults.

No wonder long-term thinking has become a scarce resource, individually and collectively. In an op-ed for the New York Times that poignantly spots Caspar David Friedrich’s iconic Romantic wanderer with a smart phone in his hand, former U.S. Deputy National Security Advisor Ben Rhodes warns that “short-term thinking will destroy America.” Many Americans feel they don’t have a future because they can no longer imagine one, he argues. The new movie Eddington by Ari Aster, a stinging portrait of our compulsive snap-attention social media culture, cited by Rhodes and still playing in theaters, exemplifies the very phenomenon it describes—it’s already forgotten.

With critical thinking and conscientiousness diminished, we risk accepting AI’s autocurated version of reality as the reality and synthetic meaning as more meaningful than the one we create on our own.

Some of us have already drifted into AI cults, seduced by sycophantic, ego-inflating chatbots that flatter them into believing they’ve been chosen for a higher purpose.

Psychologist Glen Slater, author of Jung vs Borg: Finding the Deeply Human in a Posthuman Age, cautions: “The danger isn’t AI itself, but the forgetting of what it means to be human.”

Beastopia vs. Humanity

So—what now?

We could let it all collapse.

Perhaps the current order—political, economic, cognitive—must fail for something new to emerge. Technocratic capitalism may be the final act in Schumpeter’s cycle of creative destruction. A cathartic “burning down the House” from which Phoenix can arise: a male fantasy indeed. Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Curtis Yarvin, and their ilk would rather we stop clinging to the ideals of constructive dialogue and join the demolition. Common ground is for the weak, for those without vision, they appear to be saying. Surrender to the algorithm. Be good data.

This is not dystopia; it is beastopia: a survival-of-the-fittest age where winners are predators and the rest of us—“The Last of Us”—zombies: neither fully dead nor fully alive.

Or we could choose to become more human.

We could seek shelter with people we trust. Create rituals and ceremonies to deepen connection. Gather at work, and with friends and loved ones, as often as we can. Strengthen what HoBB partner Dr. Angel Acosta calls supraintelligence—a form of intelligence as visceral as it is cerebral. Cultivate the “Luminous Mind,” he suggests—clear, contemplative, centered—and draw on relational worldviews that see the mind as existing between us, not just within us.

In a similar vein, The Cognitive Threat’s “resistance manual” proposes resilience, education, technological autonomy, and protection of real-world public spaces.

I would add: develop character. Better yet, become a character, a strong, inimitable personality, with an independent spirit and a flexible mind that can switch sides precisely because it has firm convictions. Do cool shit. Make art. Bring beauty into the world in the most unexpected places in the most unexpected ways. Create things bigger than you and moments that outlast this moment. Know that everything you create will one day come alive again like the pre-earth meteor that crashed onto earth on June 26.

Anything is better than apathy. We don’t need to fight fire with fire by developing superagency; we simply need to fortify and wield our inherently human agency, which also, crucially, entails the freedom to let go of it.

***

A few weeks ago, over dinner in New York, someone told me their purpose was to ensure humanity’s survival. I asked, “Why?” Why assume humanity is worth saving? The answers I heard felt too small, too sentimental. As humans, I thought, we have an obvious interest in our survival, but if you take a step back, it’s hard to make a compelling case for it. Objectively, no one needs us but us—and the planet might well be better off without us.

But now I find my questioning disingenuous. Something has shifted in me. Perhaps it was that meteor’s detonation. Perhaps it was seeing Toni Erdmann again, that miraculous, most farcical, and most humane of all impossible German comedies and how it reminded me of my 85-year old father who saw war up close once and will close his eyes for good before he’s forced to see it again.

I no longer need the answer to why. I will not just outsource or outsmart my humanness. I will not be lazy, complacent, and compliant. I will think more and harder.

As Louise Glück wrote in her poem Meadowlands: “We look at the world once, in childhood. The rest is memory.”

I remember now.

***

This essay was first published as Beauty Shot by the House of Beautiful Business.