“Are you a Bill Gates or a Steve Jobs?” – The Globe and Mail Book Review

Review of "The Business Romantic"

The phrase “it’s just business” marks our times, capturing the emotionless approach we are supposed to take in the office. And not just in corporate offices; non-profits and governments are expected these days to assume a business-like approach. It’s an era of big data and fact-based decision-making. Mr. Spock would be in his element.

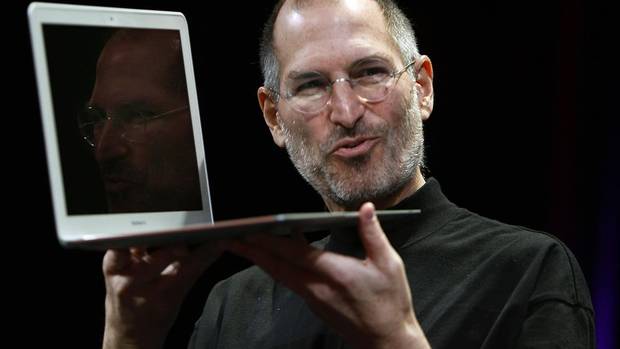

But interestingly, the most successful business person of recent years was an out-and-out romantic. Sure, Steve Jobs knew the numbers, and pulled in billions in profit. But he was motivated by beauty, artistry, simplicity and dreams of the perfect gadget. He was a business romantic.

When Mr. Jobs died, Frog Design, which had risen to fame for its work on the early Apple computers, dedicated its entire home page to a farewell message: “Thanks for everything, Steve.” For 72 hours, nobody new to the site could find links to get deeper into it, let alone contact anybody or buy services. It was a dumb business move, rationally. Even Apple didn’t go that far. But Tim Leberecht, former chief marketing officer at Frog and now a consultant, says it felt like the right thing to do. It was a romantic act.

“Business Romantics make generosity – in fact an obsessive kind of generosity – the default strategy. Helping others fosters our emotional engagement with the world and lets us connect with something greater than ourselves,” he writes in his book The Business Romantic.

The original Romantic period traces back to the early 1800s, and icons like Lord Byron, Percy Shelley, Mary Shelley, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the latter once replying to uber-rationalist René Descartes with the comment “I felt before I thought.” For them, subjective experience was more important than objective truth.

Mr. Leberecht says vestiges of that era remain today in the craze for dashing vampires like Robert Pattison, star of the Twilight movies, and coolly rational rebels like Edward Snowden. Famous figures tend to fall into one camp or another.

“If James Bond is romantic, then the whip-smart deductive reasoning of Sherlock Holmes is not; Humphrey Bogart clearly Byronic; Tom Cruise not so much. In business, you can argue that Virgin founder Sir Richard Branson or Apple’s Steve Jobs are romantic heroes while leaders such as Bill Gates, Warren Buffett or GE’s Jeffrey Immelt decidedly are not. By extension, any figure that stands apart from society, characterized by an aura of mystery and brooding emotion rather than lucidity and rational articulation, belongs in the family of romantic heroes,” he writes.

And he wants to see more romantic heroes – as well as all of us cultivating our romantic side. We shouldn’t be afraid of tapping into our emotion, he says, even putting it above reason – allowing the senses primacy over intellect. We need a heightened awareness of sentiments and moods. We should be curious about strangers and strangeness. Contrarians should be celebrated.

Above all, he says, we should believe deeply in imagination and beauty.

He encourages people “to have a romantic view of business, to act differently, but, first and foremost, to see, feel, and be different.” Perhaps fittingly, the path he outlines is fuzzy. But here are some approaches:

Find the big in the small

Look for big advances through small acts, notably ones that make experiences more intimate.

Be a stranger

Bring people who don’t know each other together and watch sparks fly. Invite an “artist-in-residence” into your firm. Encourage in-house skeptics and contrarians, even giving them positions, like a newspaper’s public editor. Wander without maps. Relate to others you don’t know through selling, a deeply romantic occupation.

Give more today than you take

Embed generosity and giving into your culture and operations. Wharton Business Professor Adam Grant highlighted the benefits of generosity at work in his book Give and Take. “Make sure you invest in what you feel strongly about. Be excessive in your intention, attention and execution. Overpromise, overcommit, overdeliver,” he says.

Suffer a little

Our customer service obsession has meant overrating the importance of convenience and underestimating the role of sacrifice. Effort leads to commitment. Get your colleagues (and customers) to try harder.

Fake it

Revel in wearing masks. Let them transform you and your brand. “Don’t get me wrong: I do not advocate that Business Romantics become con artists or masters of deception. I do, however, recommend that we acknowledge that reason has little to do with our commitment to a company or a brand,” he declares.

It’s a counterintuitive, contrarian approach. The lack of clarity is in some ways mandatory, to truly be romantic. But as our rationalist instincts rebel, something within his message will stir many of us. Being a business romantic appeals in some mystical way – and, remember, it worked for Steve Jobs.

This article first appeared in The Globe and Mail.

Image Credit: Paul Chin/The New York Times